Archives

Categories

My journey to Ramah Galim was a long time coming. I spent most of my life “Ramah adjacent.” My brother was a Ramah Ojai camper and staff member and my years in United Synagogue Youth (USY) had exposed me to some of the ruach (spirit) of the Ramah universe. Yet, I was nervous to make the leap and come to camp myself. Would I feel at home? Would I be able to connect with people? Would it live up to my expectations? Even as a potential staff member, I was nervous!

In Parashat Vayigash, Jacob has similar qualms about journeying to Egypt. His sons have just returned from trying to acquire food in Egypt, where they discovered that Joseph, who they threw a pit and thought to be dead, is actually alive AND in charge of all of the rations! When they share this information with Jacob, he finds this very hard to believe. After so much anticipation, could it all be real?! With a few more convincing words from his sons, Jacob’s “spirit is enlivened” and he decides to make the journey.

Join us in celebrating five years of Camp Ramah in Northern California where we will be honoring

Janis Sherman Popp and our fifth year camper families.

Sunday April 26, 2020

4:00pm-7:00pm

Proceeds to benefit camper scholarships – help us give the gift of camp to every Jewish child

Registration and details to follow

As I sit here in Tel Aviv, contemplating this week’s Torah Portion, Noah, and its relationship to Camp Ramah Galim, my mind rattles with endless connections. Obviously the grand Pacific Ocean, and the sightings of nature above and below, reminds us of the endless flow of rain showering down from the heavens. Whether it be whales, dolphins or seals, one can’t help but get excited about these glorious beasts. And occasionally, we are reminded of the flood with light drizzle which keeps the scenery green.

What did Noah contemplate on the ark in terms of building a new community after the water receded? What values did he dream would replace the old selfish and destructive society which God found to destroy as per the ancient text?

At Ramah Galim, community, based on love and respect of each and every individual and love of Jewish values permeates the environment. The goal is to provide a safe haven for each and every camper (and staff member) to explore themselves, others, Judaism and their personal course of exploration whether it be around nature, water or, in my case, performing arts.

This Shabbat, we conclude our reading of the Book of Numbers with the double-portion Mattot-Mas’ei. At the beginning of Parashat Mas’ei, Moses recounts the places the Children of Israel have encamped along their forty-year journey through the wilderness. While the list might seem a bit dry to us as readers (there is not a lot of detail as to what happened where), I imagine that for the Israelites, it was a reminder of all the places they had been and the things they had experienced in each place. What a fitting parashah for the end of camp!

By now, it is likely that your child has shared some camp memories with you. Perhaps they have told you about the places they went, the friends the made, or some of the things they experienced. Spending two or four or six weeks at Ramah Galim, after all, is a journey filled with growth. At camp, kids are encouraged to try new things and to take risks that will help them stretch and evolve.

The culture of Ramah Galim is founded on four primary midot (values), which influence our programming and relationships at every level. Those four midot are: Kavod, respect; Ahavat Yisrael, a love of Israel; Simcha, joy or happiness; and Manhigut, leadership.

Two years ago, I moved to Israel, where I study in the Center for Jewish Educators at Pardes in Jerusalem. Ramah Galim has become my home away from home, the place where I spend the most time outside of Israel. I always look forward to my time here, where I get to connect with this incredible community and witness, in real time, the preparation of the next generation of leaders.

This week’s parasha, Pinchas, focuses on manhigut. It presents a series of three vignettes that show different types of leadership, each with unique merits and each with a unique outcome. Everything is framed by the context of the narrative which, at the end of the book of Numbers, finds Moses looking for a successor to lead the people into the land.

My inner geek loves this week’s Torah portion, Balak, because it seems like something out of Tolkein’s Middle Earth. We read the story of sorcerer-extraordinaire, Balaam, and his foiled attempt to curse the Children of Israel. Instead of using his powers to curse Israel at the behest of the Moabite King Balak, he blesses them. How strange is it that the Torah implicitly acknowledges the existence and validity of magic? What are Balaam’s magical powers, and why is the sight of the tents of the Israelites enough for his magic powers to not just be nullified, but to be reversed entirely?

This parshah presents magic as Balaam’s ability to manipulate the world around him for his own agenda. Balaam’s magic is more than just coercion – he uses his will, in conjunction with ceremony and ritual, in order to break the laws of the natural world for personal gain. Yet, after his encounter with an angel and seeing the tents of Israel, Balaam’s magic fails miserably. Why? The holiness of the community of Israel, with its beautiful tents and networks of lives lived in holy relationship with one another, is something which could not be touched or manipulated by Balaam. This magic – the palpable experience of the sacred – causes Balaam to not curse, but bless, “מַה־טֹּ֥בוּ אֹהָלֶ֖יךָ יַעֲקֹ֑ב מִשְׁכְּנֹתֶ֖יךָ יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃ – How fair are your tents, O Jacob, Your dwellings, O Israel!”

The story of the meraglim (scouts) who are sent by Moses to scout the Land of Israel is an intriguing and complicated tale of espionage. All the scouts are impressed by the quality of the land and its bounty. When they return from their 40-day mission, two of them, Calev and Joshua, say that the people would be able to overcome the challenge of entering and inhabiting the land. But the other 10 scouts are not as sure. They spread fear and anxiety among the people. They say in the presence of Moses and all the people, “It is a land that eats up its inhabitants and all the people we saw there are of great stature. We were in our own sight as grasshoppers compared to giants.” God becomes angry and seems to punish those who could not believe that it was the destiny of the Jewish nation to inhabit the land. Moses finally persuades God to forgive the people. The whole episode turns out to be a catastrophe for nearly everyone involved.

We all have moments when it is difficult to appreciate the bounty in our lives. Perhaps this is most palpable in life’s transitions or the moments of newness when that which is familiar changes in some way. While wandering through the wilderness at Taverah, the Israelites struggle to appreciate the manna falling before them. They yearn for the delicacies of Egypt, the bounty they experiences while enslaved. As we read in the Torah this week, the Israelites’ collective resilience is tested along with their ability to persevere. They struggle to appreciate the bounty God provides them in the form of manna. They are in a new place, with a different source of food, and a new reality.

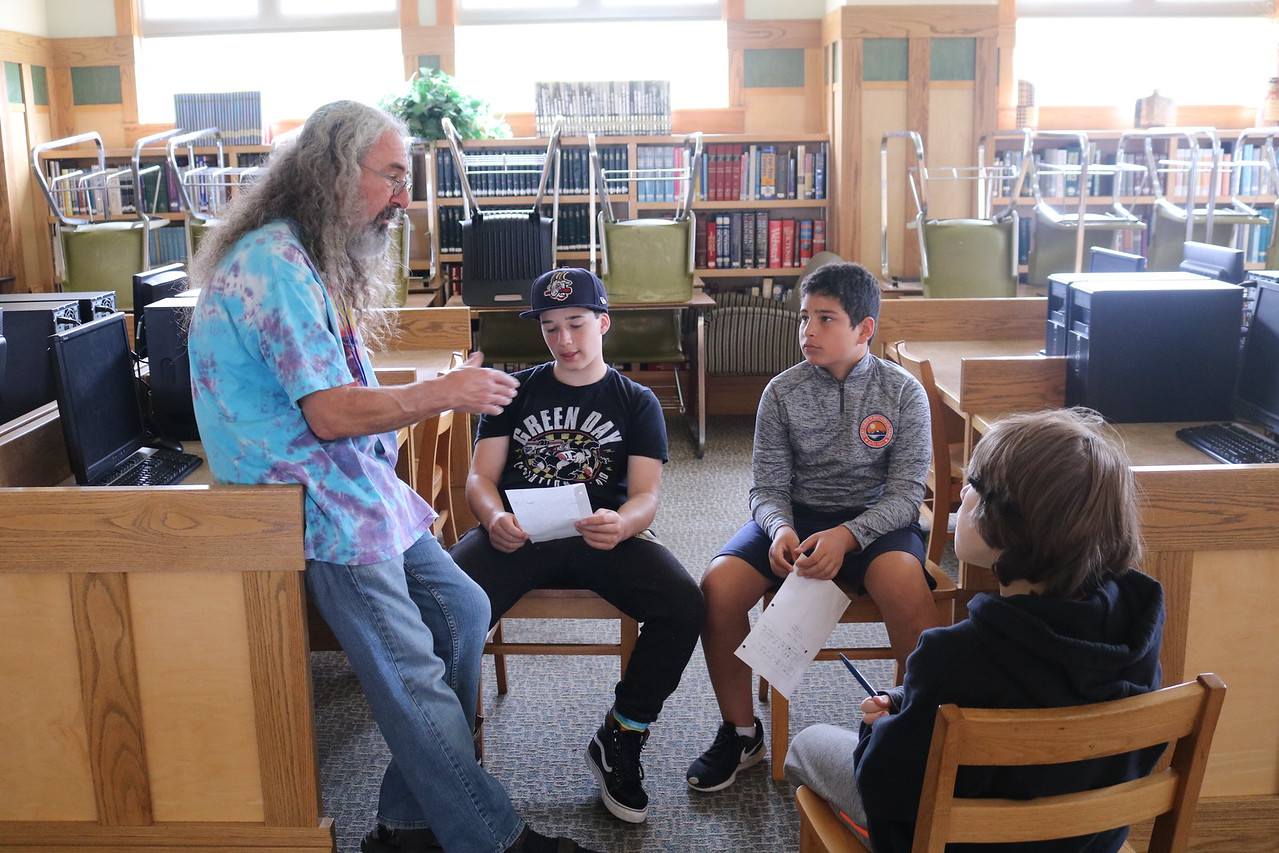

Tikvah changed my life. In 1984, I was hired to work in the kitchen at Camp Ramah in New England. A day before my arrival, I was asked if I would fill a last minute opening in the Tikvah Program. “What is Tikvah?” I asked. My experience that summer led to my pursuing a career in disabilities inclusion. I spent a total of 21 years working with Tikvah at Ramah New England and have been working as the director of our National Ramah Tikvah Network for five years. In that capacity, I work with the Tikvah directors of all Ramah camps, sharing best practices, discussing vocational training, staff recruitment, Israel trips and more. Three years ago, I was privileged to have my Ramah affiliations include Ramah Galim.

When I speak about Tikvah nationally and internationally, I point out that there was a lot of pushback in the late 1960s when Herb and Barbara Greenberg proposed the idea for Tikvah. Tikvah opened in 1970 in Glen Spey, New York and soon after moved to Ramah New England. Camp by camp, Tikvah was incorporated in to each camp. We recently celebrated 50 years of Tikvah in Israel during our recent Tikvah Ramah Bike Ride and Hike.

At Ramah Galim, Tikvah was fully a part of camp from the outset. Rabbi Sarah Shulman and the board of directors felt strongly that Ramah Galim should not open its doors without Tikvah. How far we have come in four years!